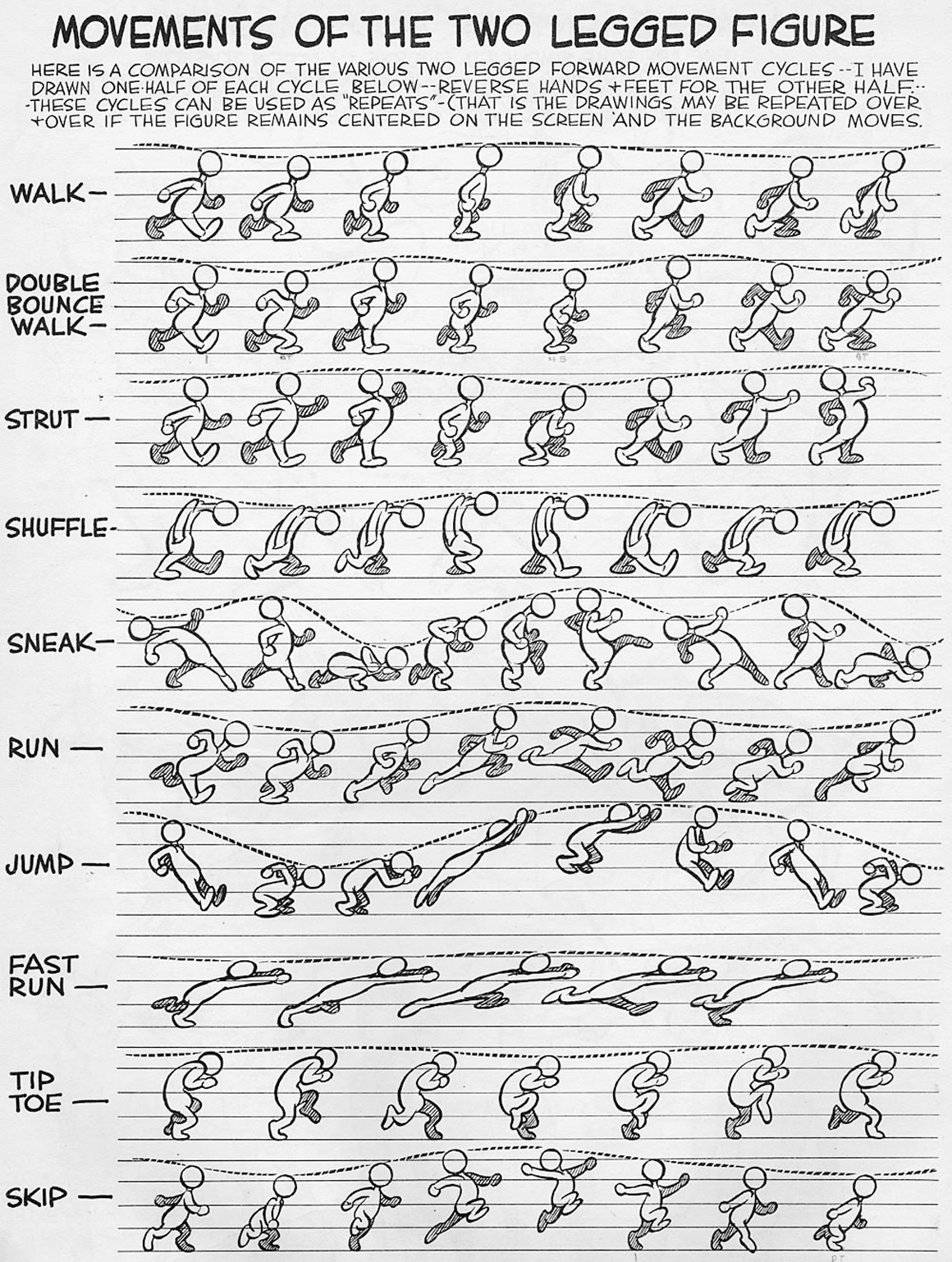

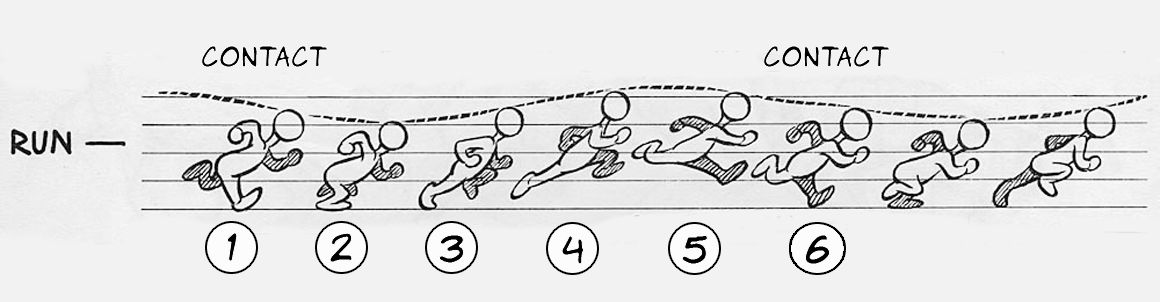

A student recently asked me about the famous Preston Blair animation books. They contain some excellent material, but frankly, the walk and run sections can be very difficult for a student or less experience animator to understand. As great as the reference animation is, Preston offered no help in timing, or in the sequence in which the drawings are to be created.

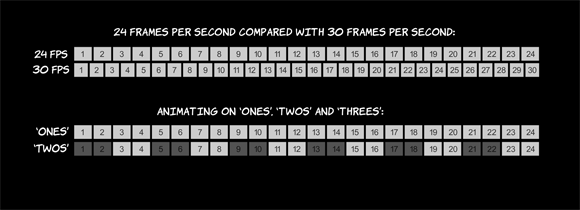

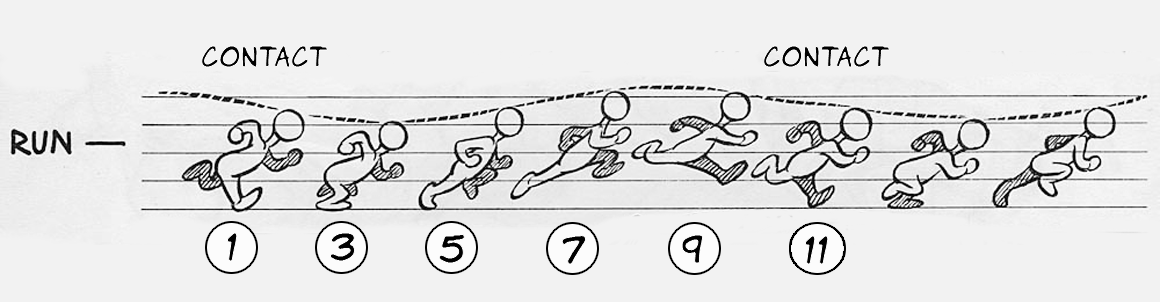

Before starting, a note on frame rates. Animators in this period animated for film, which was on 24 frames per second (FPS). Unless animating very fast actions like fights, pans or staggers, they would expose each drawing for two frames, giving an effective frame rate of 12FPS. That is the case here. In addition, it was common practice for animators to animate on odd numbers, and to add in extra drawings on the even exposures when and if needed. This will explain my numbering system below.

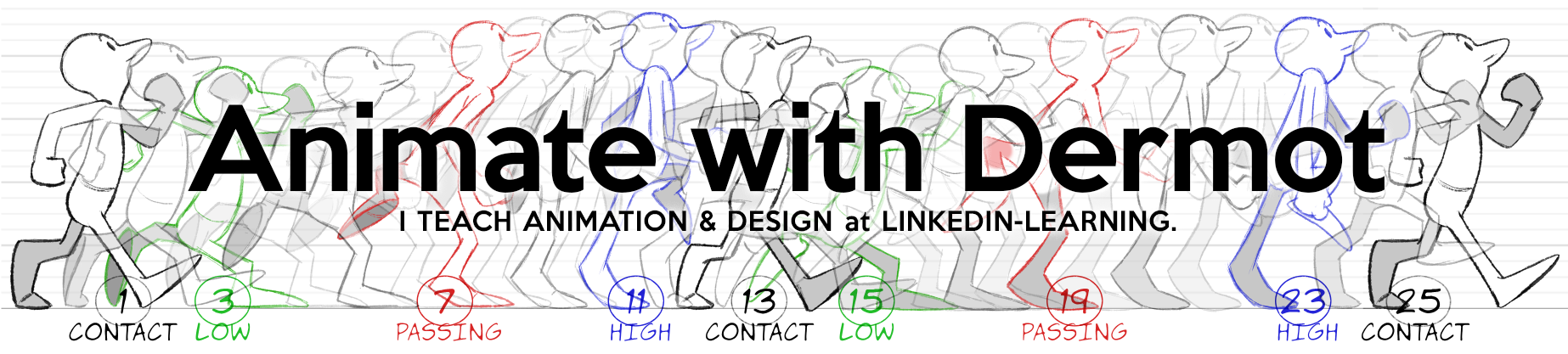

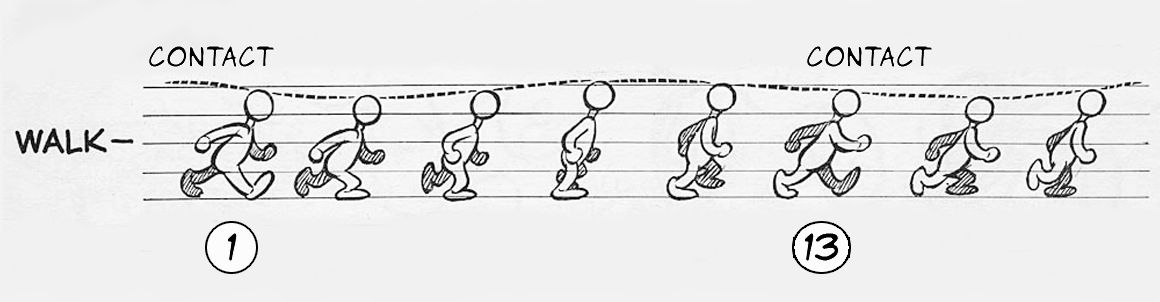

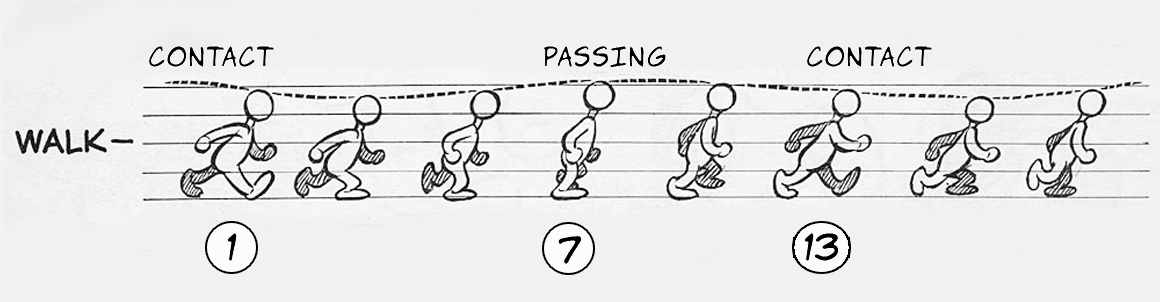

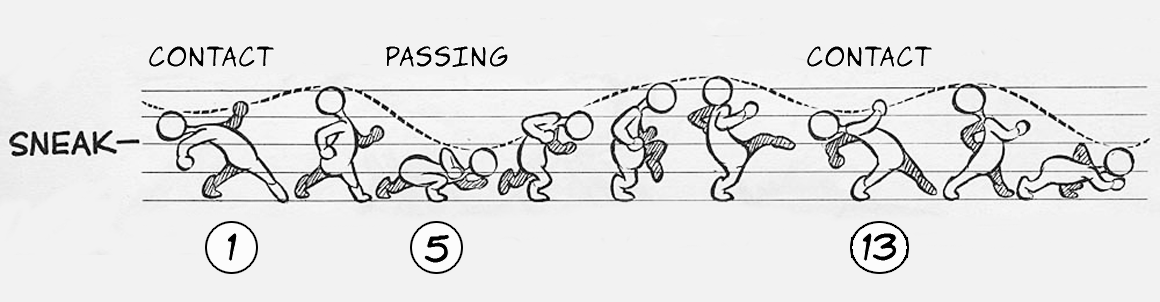

So let’s talk a look at the walk cycle and see how to break it down. The first step is easy, just find the contact poses. Those are the first poses to create, as the feet are at their most outstretched. The heel of the leading foot has just contacted the ground. Setting the timing for these poses is easy, as most standard walks are on a 12 frame beat, or a complete step in one second. On 24FPS, this means that the first drawing is #1, and the second drawing is #13. The cycle will continue to the next contact, which will be #25, completing the cycle. If you’re on 30FPS, or another frame rate, adjust your numbers as needed. Preston only provided a couple of drawings of the second half of the cycle, after #13, as you see below:

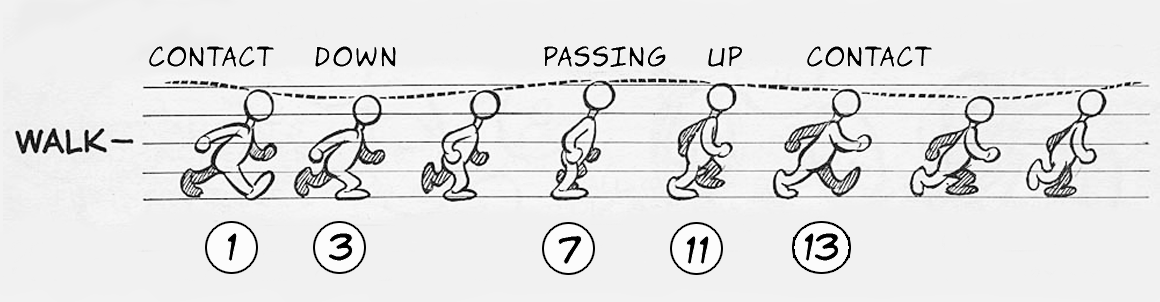

Next is to find the passing pose. This is easy enough in the walk cycle, as the passing pose is the position exactly halfway between the two contacts. Usually the arms and legs are bunched up close to the body. So the passing pose in the example below is obvious. And in the walk cycle we can place the passing pose on the exact halfway frame:

1 3 5 7 9 11 13

At this point the walk will be functional – but to add the finishing touches we need the up and down poses. (The down pose sometimes called the ‘recoil’, the up is sometimes the high point). The down pose should follow very quickly from the contact, so let’s assign that the nearest available odd number, #3. Note that you could create a really snappy timing by making it #2, but for this demonstration let’s stick to odds/twos.

The up pose is on #11. Note again that I could also make it #9, but that might make the descent into contact much too floaty. So 11 seems like a snappier timing:

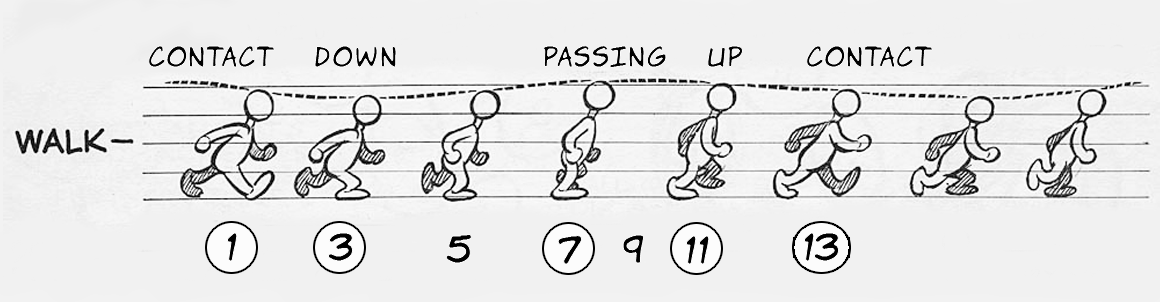

Not much left to work out – the drawing between #3 and #7 is an inbetween. We need to add another inbetween between #7 and #11, which I’ve marked with #9:

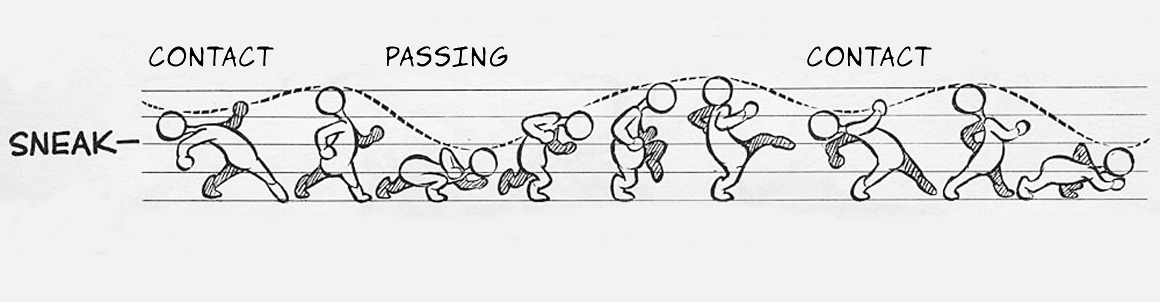

Now let’s apply the same process to a tricker walk, the sneak. In this case, I’ve labeled the third drawing from the left as the passing. You could also make the fourth drawing the passing, but it just looks like an inbetween (see how it fits like a simple inbetween between the third and fight drawings). The third drawing is the one that creates the ‘sneak’ element of this walk. Without it, the sneak would be much less of a sneak. Drawing #3 seems like a more essential drawing in setting the key action, so let’s go with that.

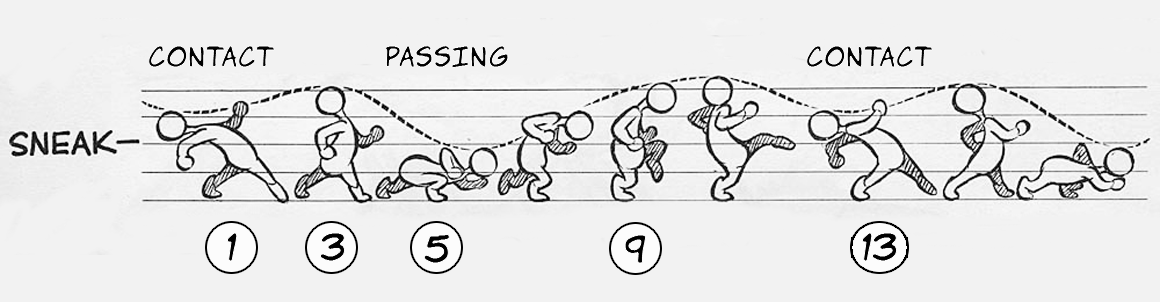

Given that we have seven drawings, and assuming that this sneak will be on the same timing as the walk (a twelve frame beat), let’s assign the frame numbers – easy:

Next we have the inbetween/breakdowns between the contacts and passing. #3 is easy, and I think that #9 will be the biggest drawing between them.

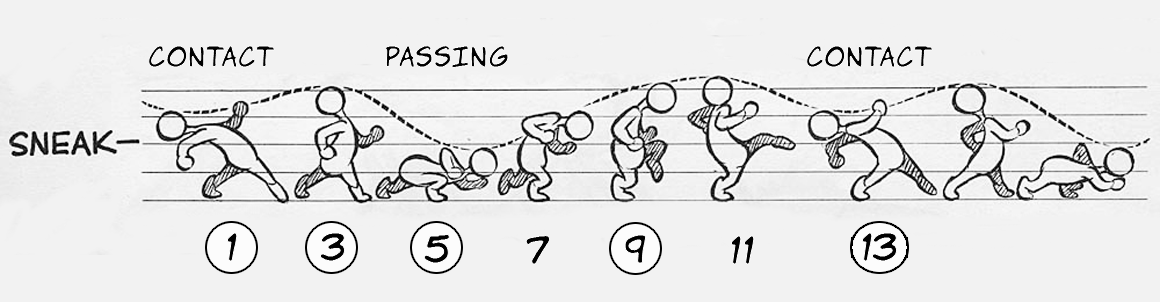

Drawings #7 and #11 are breakdowns. Note the extreme action on the leading foot on the breakdown drawing #11.

Check out the animation below for the process I used:

1. Lining up the Preston Blair images and shooting them, on twos (the odd numbers).

2. Smoothing the action by adding inbetweens, on ones (the even numbers).

3. Finding that it was too fast, I simply converted the scene back to twos, halving the speed.

Again, here’s the youtube video showing the frames in sequence, with inbetweens added on ones, and the final pass with the ‘ones’ version stretched out again onto twos, for a really nice, slow sneak.

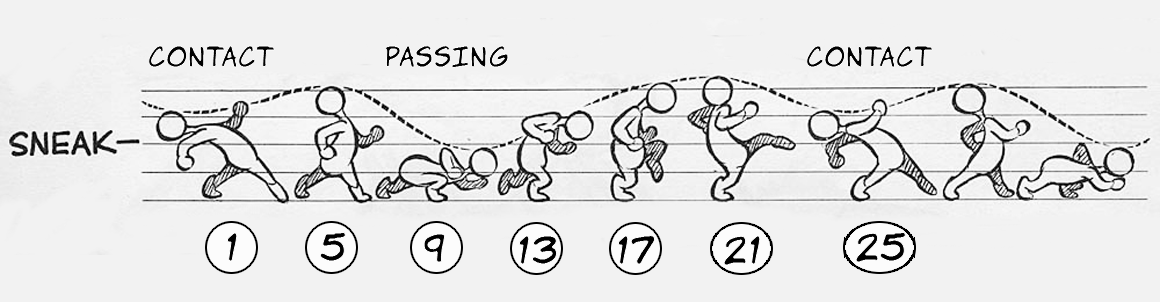

The final timing of the final slower (on twos) sneak is here:

The timing on the other actions in Preston’s book will vary depending on the actions. Runs are on faster beats than walks, for example, so his runs may hitting their second contacts 8 or 6 frames after the first. His run cycle, for example, may even be on ones, with each drawing numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, etc.

Either of these might work. Try them yourself!

Best of luck using his reference material. It is very high quality, but as you can see, you have to do a bit of lifting yourself.

For a MUCH more up to date book on walks, there is none better than Richard Williams Survival Kit. Be sure to get the expanded edition if you can, as it has a few extra pages of material.

*

When I’m not doing my own work I’m teaching animation and design courses on Lynda.com. Follow the link below for a free 10 day trial. Should you join the site after following this link, I get a small commission.